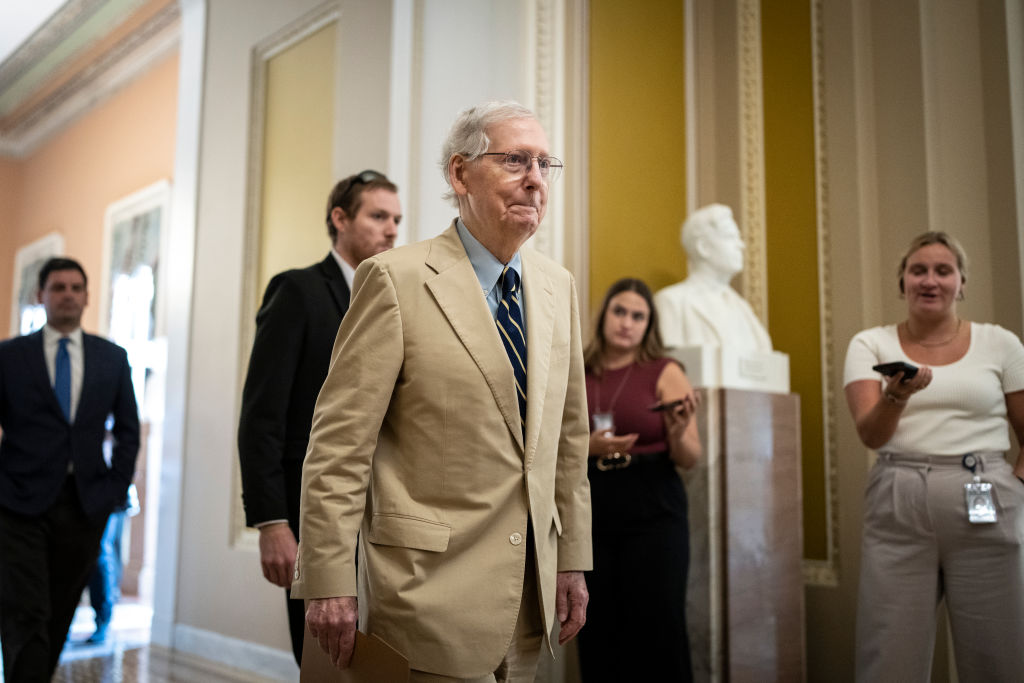

Nobody emerged from the Senate’s months-long, politically treacherous Ukraine fight more battered — and somehow upbeat — than Minority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Yes, significant hurdles remain in getting the Senate-passed foreign aid package, or something resembling it, signed into law. And there’s little McConnell can do to reverse his party’s drift from its Reagan-era foreign policy doctrine.

But the Kentucky Republican can safely say he defied the odds and overcame significant political headwinds in helping push the $95 billion bill. This includes an unrelenting wave of conservative GOP opposition after several failed and seemingly futile attempts to pass new Ukraine aid.

In the end, McConnell brought 21 other Republicans along — just under half the GOP Conference — and touted it as a victory given the circumstances. Former President Donald Trump was whipping against the measure, and McConnell’s GOP critics were only getting louder, fueling further doubts about his influence within the Senate Republican Conference. The window to get something done was, and still is, quickly closing.

“I’m proud of the fact that we got 22 votes. I know it’s a hot political issue — when the likely nominee of your party is opposed to it, that has a lot of sway,” McConnell told us in an interview just hours after the Senate passed the foreign aid bill, 70-29.

Trump has “a bigger megaphone, more sway on public opinion than any of us individually,” McConnell said, referring to the former president multiple times as the party’s “likely nominee.” But McConnell, in the twilight of his Senate career, is turning his attention elsewhere.

A new era: McConnell, the chamber’s longest-serving party leader, was reflective as he looks to cement his own place in the history books.

In many ways, McConnell represents a fading era of Republican foreign-policy orthodoxy, one that’s been further eroded by Trump. For example, nearly all GOP senators elected since 2018 and Republicans under the age of 55 rejected the foreign aid bill. It’s one of many signs the party is changing — “just not fast enough,” in the words of Sen. Eric Schmitt (R-Mo.).

McConnell, though, made no apologies for his stance. McConnell likened his opponents to pre-World War II isolationists and said his party tends to act this way under a Democratic president. McConnell added that many of their arguments against the package were “just not accurate.” And he said history would be the ultimate judge.

“I know we have a significant number of critics on our side like we did back during the Roosevelt period,” McConnell said. “But I think it’s the right thing for our country to stand up to this sort of thing. If we don’t, I don’t know who will.”

The border calculation: McConnell vigorously defended his decision to move forward with a foreign aid bill without a border security component that Republicans were once demanding as a precondition, lamenting that “our conference kept changing its view about that.”

“Our members, in the end, I think, just decided it wasn’t good enough or that our likely nominee didn’t want us to do it at all. And that kind of took the steam out of it,” McConnell said. “I was just trying to be kind of an honest broker and point out to our colleagues what was going on.”

McConnell pressed ahead with the foreign-aid-only approach even as his NRSC Chair, Sen. Steve Daines (R-Mont.), warned it would hamper the party’s efforts to win back the majority.

We asked McConnell about Daines’ warning. McConnell said the underlying effort was “extremely important to our future and to the future of democratic countries.”

— Andrew Desiderio and John Bresnahan